I recently finished an infinite runner game I’ve been making in the Unity engine for the past 7 months. In this blog, I’m gonna go in depth explaining and reflecting on the development of City Escape 2. While I’m partially writing this for my own sake, hopefully it’s interesting or even educational for anyone who stumbles upon this. I recommend playing the game first for context.

Focus

First I’m going to skip ahead and explain my ultimate lesson from this project: Focus is crucial to keeping game development going smoothly.

That probably sounds obvious, but it's a trap I've fallen into multiple times. Games are complicated and have many aspects, so it’s hard to pace myself and take things one at a time. Development of City Escape 2 was off to a good start for about a month. I was focusing on the core gameplay loop, and only spent time trying to make it feel right. Work was slow but steady, and progress is archived by version builds I’d export every few days. But the dates of these builds show evidence of a halt in progress; there’s a sudden gap of time, (not quite a month,) between version 11 and the previous one.

The notes I kept with each version made it easy for me to look back and see where & what exactly went wrong. A month in, I suddenly started thinking about playtesting. I figured I had to make the game presentable, so I made temporary player character animations, a tutorial and improved camera effects. None of these things were necessary at the time; I wasn’t ready to work on them. I had begun to lose focus.

I tend to add more and more features and systems in a desperate attempt to make my game fun. For this project it happened pretty rapidly when I started working on the code that randomly generated the level layout. A complex and important system, yet I scrambled to get it playtest worthy in only a few days. I kept adding functionality without spending time to polish or test anything. This big, crucial system barely did what I needed it to, and the code was a tangled mess. This burnt me out.

I’ve made this mistakes before, and what it leaves me with is a mess of features and systems that are only half baked. Continuing to work on the project was very daunting because there were so many things that needed to be done. And the longer I spent away from certain unfinished areas of code, the harder it was to return to it.

At this point I just didn't know what to work on. I only got less focused as I shifted to working on small details that had nothing to do with the core gameplay loop. In reality, I was doing this to distract myself from the harder, more important core gameplay I should’ve been figuring out.

I came to a revelation about this one night while looking through my old notes. I decided to get back on track, focusing on what I needed to and working on things one step at a time. Luckily, I had a backup of the project from right before things went awry. (Always backup your files.) From there I went back to focusing on core gameplay and adding features one at a time. I was careful to make sure each feature was fully implemented, tested and polished to a degree before moving on to another one. I never regained the same energy and consistent progress I had at first, but from this point on things went fairly smoothly until I was able to actually finish the project!

Concept

City Escape was my first significant, original game project. Though “original” may be a stretch, because halfway through development I restarted the project and followed a tutorial. Since then I’ve learnt a ton, especially from the following project, Death Chamber. Afterwards, I wanted to make something simpler, but give it more polish. A successor to my first game was a safe idea, since it’s something I knew I could make. Only way I could go was up, right?

I started thinking about the project and scribbling out ideas as late as March 2019. That said, I wasn’t married to any of these ideas. In the past, I’ve made the mistake of thinking up game designs in my head and imagining all it could be, instead of letting prototyping lead the design. (See the last link.) This time I wasn’t going to make that mistake. I only had a vague idea of the core gameplay, and I would experiment to figure out the specifics. I had a stronger idea of the feeling I wanted the game to provide: fast paced action with occasional panic.

The main design idea came from dissatisfaction with the fact that in most infinite runner games, game overs are immediate. At any given point, a small mistake in player input can immediately make them lose. My theory was that, despite being more difficult, this design actually makes games less tense and engaging. The survival state of a player is binary; either they are still playing or they lost, no in-between. I don’t know about you, but I feel way more tense and invested in a game when I only have one life left compared to five. It changes my mood and behaviour. In most games, the player can be doing well or be close to failure as a result of their actions. This takes many forms, and can be based on many factors depending on the complexity of the game.

My thinking was, could I apply this kind of non-binary survival state design to an infinite runner game? I realized that the unforgiving difficulty may be a draw of these types of games, but I wanted to make a game that’s more approachable and engaging. My idea was to use speed as the survival / success factor. The player’s goal is to go as fast as possible, and going too slow would lead to failure. Inspired by playing Dino Run when I was younger, the main concept of the player being chased was an obvious fit for my game.

The main inspiration and reference for this game was Canabalt. I must've read through Adam Atomic’s blog on the game’s development a hundred times, and I ended up stealing some of his ideas. Having that game as a source of inspiration was a bit disheartening though. My game project was taking me months and months, and Adam Atomic was able to make a much better game in five days.

Early experimental phase

Technically, development started a year from release. Not long after starting, my hard drive corrupted itself to the moon and back. I lost everything on it. Thankfully I hadn’t worked on it too much at that point, and was able to easily redo that initial work when I returned to the project months later.

For a game with speed being a main mechanic to work, there had to be ways to gain and lose speed. Obstacles would be sprinkled throughout the level, and they slowed the player down significantly if not avoided. Speed would be gained automatically from acceleration, but I needed a risk-reward mechanic that would payoff skill with more speed.

My first solution was a parkour landing roll, inspired by Mirror’s Edge. Timing a button hit after landing from a high place would boost your character forward. This mechanic made verticality more important and was the type of solution I was looking for, but presented its own issues. I didn’t know how to effectively telegraph if / when the player could pull it off, since they needed to be falling from a great enough height. More importantly, it confused the game’s goals. Intentionally jumping from the platforms to the ground and rolling was rewarded, but the main goal of the game was to stay on the platforms. I had a hunch both of these things would cause confusion to players.

I went back to the drawing board, and soon had a breakthrough. Instead of asking the player to risk falling, I could ask them to risk hitting obstacles. By timing a button hit right before running into an obstacle, the player would boost instead of tripping. This made the game more engaging by frequently giving the player the choice to either jump over an obstacle or try to “vault” it, the kind of risk-reward system I was looking for. It also gave the obstacles more purpose. Late into development this move was balanced by being made more strict and punishing in some ways.

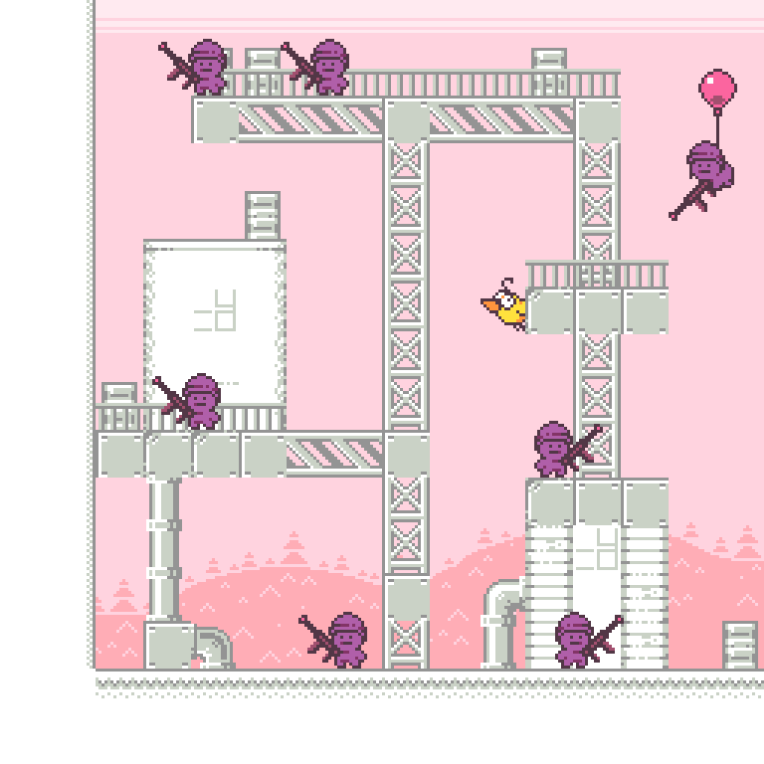

Here’s what the game looked like around this time

Early on I wasn’t sure whether this game would be an infinite runner or be separated into levels. Infinite runners are more common and that might’ve been a little easier to make, but I liked the idea of making multiple levels of differing difficulty and visual distinctiveness. Ultimately I settled on a level structure, as I felt it would give the game more varied pacing.

Physics and collision detection, as simple as they need to be for a game like this, were implemented poorly and remain wonky in the final game. The Unity engine provides physics tools that are easy to misuse, as I did. Later in development, replacing collision methods with something more reliable seemed like pulling a tablecloth out from under a house of cards. While I was able to improve it in some ways, the final product has very rough physics. Tightly tuned physics can be important to making a game feel just right. In the future I’d like to learn more about how to do that, maybe by not relying on a system included with the engine.

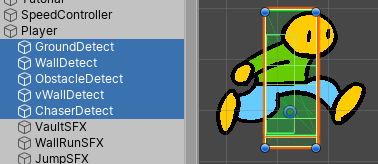

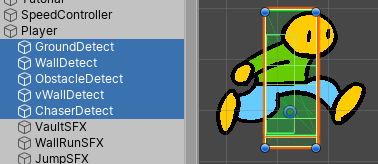

Each of these is a separate hitbox. I think all but one are deprecated, but I never bothered to remove them…

As I explained earlier, I lost focus a month into development. I reached a point where everything was in place for the game to be presentable, but I wasn’t happy with any of it. I had burnt myself out trying to get it to that point by self-imposed deadline. I was not happy with the game, but threw caution to the wind and got someone to playtest it. They stared blankly at the screen while he played, no hint of fun or engagement. I knew the game sucked, but having someone’s reaction confirm it was very discouraging. I cite a loss of focus as the reason for I made no progress during the following months, but looking back, I realize that discouragement had an impact on my motivation.

The “No progress” phase

Cute name, huh? I didn’t get significant work done on this project for 3 months. As I explained earlier, my focus kept shifting between small details and visual experiments that didn’t end up contributing to the final game. It began to feel like this game would never be finished. There were a lot of moments where I felt the need to cancel the project, not realizing why development stopped going well.

Overwhelmed with everything that needed to be done on the game, I distracted myself by trying to figure out the game’s visual style. I was initially excited to make the game visually appealing, maybe even cinematic at times. I have some ability with visual art, but ended up struggling to come up with a visual style I was happy with. I focused on the player character design, the look of the cityscape and a general style that wisely used contrast & value to make the game visually clear. This was frustrating, and most of the effort was wasted because I ended up using a simple style and sticking with temporary player assets.

At one point I noticed a problem where test builds were displaying at a different scale than I had set them to. I posted to a bunch of support forums, chats, and wherever I thought I could get help from. Couldn’t for the life of me figure out the problem, and it bothered me so much that I couldn’t focus on anything else. Eventually I found out why: my laptop’s display setting was at 125% scale. A stupid mistake, but from it I’ve learnt not to let small details or issues stop me from constantly moving forward.

I honestly don’t remember much about what I worked on at this point. I eventually just stopped working entirely, but knowing that this project wasn’t finished kept nagging at me. Realizing why the project stopped going well, I became determined to get back on track and finish it. I dug up an old backup of the project and restarted development from there.

Late experimental phase

The project’s title became “Hot Fuzz Rush” after resetting to distinguish this new phase of development. City Escape 2 was not intended to be the final name, but my inability to think of good names prevailed. I think of this game as a successor, not really a sequel.

When I regained focus on the project, one of the first things to do after fixing up old code was remake the level generation system. It was at the core of the game, yet the code was sloppy and rushed. I reused code where I could, but most of it was remade. This time I focused on making sure each aspect was polished, one at a time. Some of the game’s mechanics were disabled until I was ready to rework them in.

Randomness is a great tool in game design, as long as it’s randomness within strict control. For example, something as simple as the vertical placement of platforms is subtle but important in this game. Simply having the code spit out a random Y value within a certain range resulted in platform’s that were often very similar in height. I spent significant time trying to mitigate this, and vertical platform placement actually became the most complicated part of the level gen code. Other systems in the game had to feel random but provide the player with a fair experience. Platforms low enough to reach from the ground, for instance, are guaranteed to appear around a certain frequency.

The police force chasing the player is an important element to the game’s feeling, and I found it difficult to balance. It’s obvious function is a failure state, the punishment for not being fast enough. But I felt that it’s more important role was to keep the player tense. To accomplish the former function without feeling unfair, it couldn’t reach the player too fast. If I wanted the game to still feel tense when the player was doing really well, I needed it to speed up. “Rubberbanding” was the solution I needed to make it feel just right. It’s a controversial game design trick, but I’m confident it was the right choice. City Escape 2 is less tense yet more frustrating without it.

Another game feel feature I added around this time is what I call “velocity hold.” It’s a subtle effect that holds the player at the peak of their jump for a few frames if they’re still holding the jump button. I wanted to add a sense of suspense to jumps, where the player is held at the peak for a bit before falling.

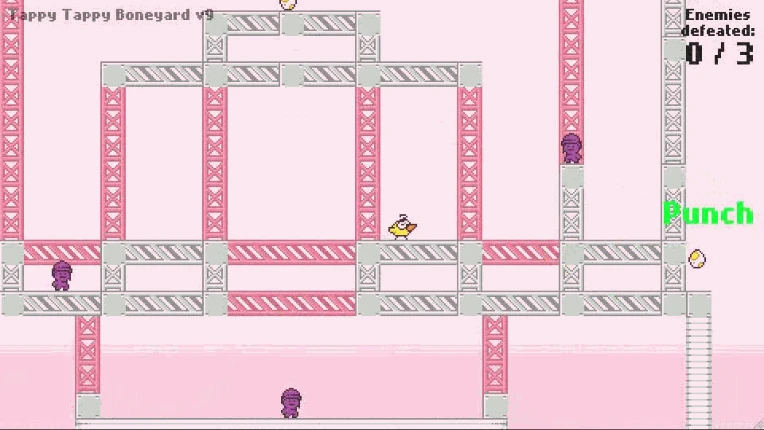

It was around this point I cut one of the player moves from the game. I haven’t mentioned this yet, but a wall run mechanic was in the game since version 1, even before vaulting. Walls were set up throughout the level, and by holding a separate button the player would preserve their velocity until they reached an edge of the wall or jumped. it could be used to gain a lot of distance and height. It was a cool move! But that’s all it was. It didn’t have a specific gameplay purpose, and as the design evolved it became apparent that this feature didn’t really fit. The mechanic was inspired specifically from Mirror’s Edge 2D, which was made by the same guy as the Fancy Pants Adventure games!

This was better than Catalyst

Version 18 is when things really started to come together. I made the player jump much higher and snappier. It was an immediate improvement, and I couldn’t believe I hadn’t done it sooner. The builds before this point feel shockingly bland in comparison.

Up until this point in development, all the player could do to get back up if they fell to the ground was dodge the many obstacles down there until they got to a platform low enough to reach. I had a feeling that players would find this boring and frustrating. Around this time, I noticed a glitch where the player’s jump would sometimes be much higher than it should be. I eventually figured out that it triggered by jumping into the side of an obstacle, causing the code to not reset the vertical velocity. After figuring this out, I found myself using it myself in gameplay to get back up from the ground to the platforms. It hit me that this solved the problem of the ground being too frustrating; it was a skillful move that let players get back up manually. It was a natural risk-reward mechanic, too. Originally a glitch, “springboarding” turned out to be the final piece of the puzzle.

Not long after this breakthrough and fixing up some other systems, I finally felt like the game was fun. To put that into perspective, I reached this milestone on 4/20 (haw-haw) which is exactly half a year after I clicked “new project.” The game was far from perfect, and of course it would never be all the things I wished it could be. But after all that time I had something that I enjoyed playing. The game finally felt the way it was meant to. I could finally stop experimenting.

Polish phase

By this point, I was eager to get the project over with. For that reason, the ratio of time spent experimenting with gameplay vs time spent polishing is way unbalanced. I spent so much time trying to make the game fun, but little time on the visuals, audio and whatever else that would really make the game shine.

Making the game’s tutorial was a pain and took much longer than I had hoped. It required the reworking of systems that weren’t set up to handle the tutorial’s unique gameplay. At first I thought that the tutorial should be incorporated into normal gameplay, and my early attempt at a tutorial paused the game every now and then without warning to show text. I shouldn’t have to explain why that’s bad design. The final tutorial was designed to be seperate from the main game but be 100% interactive. I’m happy with how it turned out.

Vector graphics in Unity became much easier sometime before development began, as SVG files became supported. I liked that Flash games still looked sharp when played at a higher resolution, (try turning on fullscreen mode in the Newgrounds Player app,) and I wanted my game assets to have a similar effect. Admittedly, I was overly excited about it, and started making my assets vectorized without considering if it was a good idea. For geometric graphics, I made assets in my graphic design program, Affinity. For authentic flash style sprites, I animated in Flash mx 2004 and used a separate program to convert each frame from a SWF to SVG file.

The problem is, Unity is made to render triangles, and these vector assets are rendered as if they’re a flat yet polygonal model. Even a simple drawing will use a lot of triangles. As far as I know, they also can’t be animated like a sprite sheet. Accomplishing the same effect requires different vector sprite objects to be set to visible / invisible. Both of these factors could potentially cause performance issues. So I guess it didn’t make a ton of sense to make the player sprites vectorized…

Wireframe view. Compare this to the two triangles needed to render a normal sprite

The exact effect this has on performance, I’m not sure. But it’s certainly far from efficient. I think vector graphics in Unity are great for some things, but not others. While my dream would be to make a game that’s 100% vector and thus has a lot of camera zooming freedom, for the near future I should figure out how to use this graphic method smarter.

Actually, you shouldn’t even be seeing that version of the player sprites. They were meant to be temporary. Sticking with temp assets is one of many ways I cut corners with the visuals. I just wanted the game done, and figured that these sprites were serviceable. The player character appears very small on screen, so it was even harder to justify spending a lot of time making him look good. Still though, seeing these 3 frame animation loops pains me, especially because I know the sprite animation in the original City Escape is better.

Originally I wanted to do a lot of interesting things with the visuals, such as incorporating graphic design into the world like the original wipE'out" games. But late into development, it was more about getting this game presentable at all, let alone making it look good.

All that said, this game looks more finished and has more detail than anything I’ve made before. I’m disappointed that it doesn’t live up to what it could’ve been, but this is still breaking new ground for me. I guess I should be proud of that.

From early on I had the idea to make every level visually distinct by changing the colour scheme. To accomplish this, the level’s visual elements are all made white, allowing them to be set to different colours at runtime. Deciding on the colour schemes seemed like it would be fun, but ended up being really difficult. It’s a shame that I never bothered to change colours of the character sprites to match; they stick out like a sore thumb, especially in level 4.

The visual execution of the thing chasing the player was a challenge, and I’m not confident that my solution was effective. Since early on you could always see how fast it was going and whether it was gaining on you or not. In the final game it takes the visual form of cop cars and choppers. The player is running from a blinding wall of police lights, and the cop vehicles all travel at the same speed as it. I’m not sure how clear that is to the player. I also find it awkward how slow the vehicles are moving.

Moving trains are a visual element I have a lot of fondness for. It might have to do with how much I enjoyed Thomas the Tank Engine as a kid, or living in a place with a really nice view of a train that passes by multiple times a day. The train in the original City Escape was one of the first things I made, present from the very first build. Of course I had to include a train in this one. It’s cool that I was able to give it an actual gameplay purpose, being the player’s means of escape at the end of each level.

By the end of development, I was sick of how messy my past programming was. It made changing or adding to it a pain. Yet wanting to get this project over with, I kept writing messy, garbage code. In the future I’m going to get better with planning out code systems ahead of time, and keeping my code clean, lean and mean.

I have very little to say about the game’s audio because I spent little time on it. The final product still uses sound effects that were meant to be temporary. I hate working on audio. This may be the aspect the most corners were cut on. I hope it doesn’t drag down the game experience much. Thankfully, I had help with the music.

Before this project, game development had been a complete isolated process for me. I always wanted to work on projects with other people though, and prior to this project I had become fed up with doing everything on my own. I’m happy that this project turned out differently! I reached out to users, and others reached out to me. @CryNN and @Technomatics offered to make original music. I stumbled across @RaIix’s Unity package which made NG.io easy and authentic to classic Newgrounds games. He was really cool about letting me use a beta version, and was incredibly helpful in helping me with technical problems and offering feedback on the game. I ended up using code and audio from some other users too. All of these interactions were thanks to Newgrounds. So it’s fitting that the game is NG exclusive, at least for now.

I’m excited that I was able to get Newgrounds.io working for the first time, though I feel that it wasn’t utilized to its fullest potential. The scoreboard was a last minute decision, and unlocking medals for beating levels isn’t all that interesting.

I’ve always had trouble with playtesting my games. The design decisions of City Escape 2 could’ve been better informed if I playtested at every stage of development with a bunch of people. But it can be hard to find good candidates among the people I know, and I don’t want to bother anybody by asking them to play my game. At the tail end of development, I did a little playtesting remotely. This is difficult, as I can’t watch them play and only have their feedback to go off of. A lack of clarity in communication became an issue, making it even harder to get to the root of the issues playtesters had. I’m not sure how to do playtesting better.

I hope this post mortem didn’t seem to down on myself, as I’ve pointed out a lot of mistakes and ways I’m not happy with the final product. Ultimately, this game is more polished than anything I’ve made before, and development has gone better than ever. I had a somewhat unique idea and worked hard to get it feeling the way I envisioned. I’m proud of that. Looking at my initial “design doc”, it makes me happy to see the things I was hoping to make and did. Figuring out Newgrounds.io for medals and scoreboards, programming save data, controller input, an interactive tutorial and such were all pipe dreams at one point.

I learned less big development lessons from this project than my last, but I see that as a good sign; much less went wrong this time. I learnt from the mistakes of my last project, and created a more polished game in a fraction of the time. I know that next time I make a game, I can do it even better >:)